|

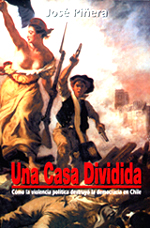

HOW CHILE WAS SAVED FROM COMMUNISM by José Piñera "José Piñera, at long last, demonstrates convincingly that the removal of Allende in 1973 was the result of Chilean institutions disgust with Allende's repeated violations of democratic procedures and efforts to establish in Chile a totalitarian regime". (Richard Pipes, Professor Emeritus of History, Harvard University) |

The complete version of this essay is here. It was published in the journal "Society", September/October 2005, Vol.42, No 6. Below a condensed version. [in Italiano] [en Español] Historic Documents |

|

"When a long Train of Abuses and Usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object, evinces a Design to reduce them (the People)under absolute Despotism, it is their Right, it is their Duty, to throw off such Government." ( The Declaration of Independence of the United States of America) 1. The Chamber of Deputies Resolution of August 22, 1973 At noon on Wednesday, August 22, 1973, the Chilean Chamber of Deputies was convened to consider a Resolution that would change the course of Chile's history. The first speaker was a Christian Democrat member of the Chamber, University of Lovaina’s sociologist Claudio Orrego. He stated that the proposed Resolution, jointly introduced by the centrist Christian Democrat Party and the rightist National Party, was necessary because "the country is in a crisis that has no parallel in our national history, in the 163 years of independence”. Orrego denounced that marxist President Salvador Allende had not respected the Statute of Democratic Guarantees that had made his election possible. That listing of individual rights had been incorporated into the Constitution in 1970 by the Christian Democrats as a condition for their support for Allende's election to the Presidency. Because Allende, the candidate of the Socialist and Communist parties, had only obtained 36.2 percent of the popular vote, Congress had the power to choose the president from among either of the two relative majorities. Later, Allende would confess that he had only signed the Statute as a "tactical" move (Regis Debray, The Chilean Revolution: Conversations with Allende, 1971). After Orrego, several members took the floor. Hermógenes Pérez de Arce, from the National Party, affirmed that "the Administration has violated the Constitution and the laws, which has given way to the illegitimacy of both the mandate and exercise of the President of the Republic." Luis Maira, from Unidad Popular (the governing Popular Unity Coalition, hereafter abbreviated to UP in accordance with the usual abbreviation in Chile), did not deny the grave accusations made by the proposed Resolution, but he tried to justify the conduct of the government by maintaining "that the problem in essence is none other than the Rule of Law and its just correlation with indispensable economic transformations." At 2:13 p.m. the debate was interrupted. In the Hispanic world, not even such grave matters warrant missing lunch. The afternoon session, convened in order to vote on the proposed Resolution, began at 8:00 p.m. But there was a surprise. After a brief debate, the Chamber called for a secret session at the urgent petition of Jorge Insunza from the Communist Party. When the public session resumed, the members immediately proceeded to vote. Once the count had been made, the President of the Chamber declared the Resolution approved by 81 votes to 47. At 9:49 p.m. the session ended. The following day, August 23, the page-wide headline of El Mercurio, Chile's paper of record, read: Resolution by Chamber of Deputies. The Resolution, approved by almost two-thirds of the members (63.3 percent), accused President Allende's administration of 20 concrete violations of the Constitution and national laws. These violations included: support of armed groups, illegal arrests, torture, muzzling the press, manipulating education, not allowing people to leave the country, confiscating private property, forming seditious organizations, and usurping powers belonging to the Judiciary, Congress, and the Treasury. The Resolution held that such acts were committed in a systematic manner, with the aim of installing in Chile "a totalitarian system". It is an extraordinary fact that the Chamber's Resolution had been approved by all of the members from the Christian Democratic Party, the majority party whose undisputed leader was Senate President and former President of the Republic Eduardo Frei Montalva. Only three years earlier, on October 24, 1970, that same party had given all of its votes in order to elect Salvador Allende president in the Congress. For John Locke, the great English political thinker, tyranny is "the exercise of power beyond the bounds of law." When such a tyrant appears, it is he who places the country in a state of war by exceeding the limits of his power. That is to say, he has "rebelled," in the strict Latin sense of the word ("re-bellare" coming from "bellum,"war"). The essence of the Resolution, therefore, was the accusation made against President Allende that, in spite of his having been elected democratically, he had rebelled against the Constitution and thereby become a tyrant. The Resolution of the Chamber of Deputies has 15 Articles and can be broken down conceptually into the following four concepts: a) a Preamble contained in Articles 1 through 4, which describe the known conditions essential for the existence of the Rule of Law. It contains a warning charged with significance: "a government that assumes powers not granted to it by the people engages in sedition." It also contains a reminder that President Allende was not elected by a majority of the popular vote, but by the Congress, "subject to a statute of democratic guarantees incorporated into the Constitution." b) twenty Accusations of violations of the Constitution and the laws: one general accusation (Articles 5 and 6); seven accusations of violations of the separation of powers (Articles, 7, 8 and 9); ten accusations of actual violations of specified human rights (Article 10); and, finally, two accusations of seditious acts (Articles 11 and 12). This listing has a structure similar to the chain of accusations against King George III made in the Declaration of Independence of the United States of America. c) a Clarification regarding the role of the military ministers that President Allende had nominated to key cabinet posts (Articles 13 and 14). It should be pointed out that a year earlier Allende himself opened the doors of politics to the military by placing various generals and admirals in key ministries. For several months, he had even appointed Army Commander-in-Chief Carlos Prats to the Ministry of the Interior, a highly controversial and important political office. In August 1973, an admiral was made Minister of Finance, an office that was key to the economic management of the country. d) a Plea to the military ministers (Article 15), who were also the commanders-in-chief of the Army, Navy and Air Force, to put "an immediate end" to these serious constitutional violations. On August 23 a messenger from the Chamber of Deputies brought an envelope to “La Moneda”, the traditional presidential palace. Addressed to the President, it contained the text of the Resolution approved the night before. The next day, President Allende released a letter directed to the nation stating: "To ask that the Armed Forces and National Police carry out key functions of the government, without the authority and political direction of the President of the Republic, is to ask for a coup d'etat." Allende understood well point d) of the Resolution. The President went on to accuse the majority in the Chamber of Deputies of trying to remove him from office without a formal constitutional accusation. In this he was correct. The Chamber had resorted to a "plea for intervention" to the military ministers, and through them, to the Armed Forces, because the strictly juridical method of removing the President from office was unavailable. According to Article 42 of the Constitution of 1925, removal of the President required a vote of two-thirds of sitting senators. But because Senate elections were staggered, it was virtually impossible for a President, no matter how unpopular, to find himself without the support of at least a third of the senators during his term. As it was, the opposition to President Allende won an absolute majority in the parliamentary elections of March 1973, winning almost two-thirds of the Chamber of Deputies. But the opposition had no such majority in the Senate. In effect, the Constitution of 1925 allowed an administration to violate it-even systematically, as a wide majority of deputies maintained-as long as that administration maintained a third of the senators in its corner. It is revealing to note the confusion about the meaning of "Rule of Law" reflected in Allende's response, since he declared that he would insist upon his illegal route since, "by means of the expression 'Rule of Law' is hidden a situation of economic and social injustice among Chileans that our people have rejected. They are trying to ignore that the Rule of Law can only fully exist in such measure as we can overcome the inequalities of a capitalist society." That declaration was consistent with the one made by his Minister of Justice on July 1, 1972: "The revolution will remain within the law as long as the law does not try to stop the revolution." 2. Allende and the Left opt for political violence How is it that a President who came to power through a democratic election would then use his power against the very Constitution and the very laws that allowed him to attain that office? The answer is that a Marxist revolution, which seeks to establish what its own doctrine calls "the dictatorship of the proletariat," by definition cannot occur within the Constitution and within the law of a democratic republic. It is one thing for a Marxist leader as Allende to become president of a democratic country by obtaining 36 percent of the vote, and being approved by the legislature in a run-off decision, but it is quite another to acquire the amount of power necessary to abolish democracy and establish a totalitarian system. For that, it would require an overwhelming majority to make the necessary changes to the Constitution and the national law. This has never happened in the history of humanity, and all such regimes have risen to total power by means of violence. The keys to understanding the origin of the democratic breakdown were two official resolutions of the Socialist Party of Chile, adopted unanimously in its annual Congresses of 1965 and 1967. Already in its Congress of Linares (July 1965), the Socialist Party of Chile, which defined itself as Marxist-Leninist, had maintained the following: "Our strategy in fact rejects the electoral route as a way to achieve our goal of seizing power... The party has one objective: in order to obtain power, the party must use all the methods and means that the revolutionary struggle requires." But it was in its Congress of Chillán (November 1967) that the seditious posture reached its highest expression. There were 115 delegates attending, as well as "brother delegates" from the Communist governments of the Soviet Union, East Germany, Romania and Yugoslavia, and from the Baath Socialist Party of Syria and the Socialist Party of Uruguay. The resolution adopted stated that, "revolutionary violence is inevitable and legitimate... It constitutes the only route to political and economic power, and its only defense and strength. Only by destroying the democratic-military apparatus of the bourgeois State can the socialist revolution take root... The peaceful and legal expressions of struggle do not, in themselves, lead to power. The Socialist Party considers them to be instruments of limited action, part of a political process that leads us to armed struggle. The politics of the workers' front is carried on and is contained within the policy of the Latin American Organization of Solidarity (OLAS), which reflects the new, continent-wide armed dimension of the Latin American process of revolution" (Julio César Jobet, History of the Socialist Party of Chile, 1997). Socialist Party ideologue Clodomiro Almeyda, who would be Minister of Foreign Affairs under President Allende, speculated about the manner in which that process would end: "It is impossible to say in absolute terms what fundamental form the final phase of political struggle will assume in a country like Chile, when the current process gives way and the order of the day is the problem of power. I am inclined to believe that it will most probably take the form of a revolutionary civil war, Spanish-style, with foreign intervention, but much more rapidly and decisively"(Revista Punto Final, November 22, 1967). It should be pointed out that the Socialist Party was the second-largest party in the country, that it would be the principal party in the UP coalition that governed Chile from 1970 to 1973, and that Salvador Allende was its most noteworthy militant. Its allied party, the Communist Party of Chile, was the largest and best-organized of all the communist parties in Latin America, and the third largest in the Western world, after those of France and Italy. All of these events happened, of course, in the context of the Cold War, in which the Allende administration had allied itself with the Soviet Union against the United States and democratic Europe. In a speech in the Kremlin on December 7, 1972, Allende even called the communist superpower the "Big Brother" of Chile. Having met with supreme Soviet leaders Leonid Brezhnev, Alexei Kosygin and Nikolai Podgorny, Allende said in his speech that he held an "identical point of view" to that of the Communist leaders. But this support for the communist regimes was nothing new. In March of 1953, a week after the death of Joseph Stalin, Socialist Salvador Allende was one of the principal speakers at a ceremony in honor of the Soviet dictator. It is illustrative to recall the incredible homage to Stalin made by a key Chilean communist leader, Volodia Teitelboim: "Today the eternal glory of Comrade Joseph Stalin sleeps in the radiant chamber of the Hall of Columns in Moscow. It has scarcely been one day and a few hours since the beloved leader of the world's workers passed away - the greatest, most profound, and most noble friend of humanity... The father and leader of all progressive mankind has died. As Mayakovsky said of Lenin, he was the most human of all men... He gave abundance and a existence to his people. Beneath the eternal flag of mourning for Stalin, the nations of the earth march down the shortest road to sure victory, toward the world of human happiness" (El Siglo, March 1953). During the decade of the 1960s, Allende agreed to serve as president of the Latin American Organization of Solidarity, a pro-Castro organization designed to export Communist revolution to the continent, The organisation had publicly declared that "armed revolution is the only solution for the social and economic ills of Latin America." Claudio Véliz, a historian and personal friend of Allende, maintained that Allende's trips to Cuba had "a fundamental impact on his plans for Chile. After seeing Cuba, Allende thought that he could take a short cut. But the truth is that he went against Chilean tradition... There is no doubt that the UP government was a disaster and one which led us into civil war" (El Mercurio, November 28, 1999). As president of the Senate in the 1960s, Allende on various occasions expressed his support for the Leftist Revolutionary Movement (MIR), the group that initiated guerrilla violence in Chile. Of course, violence had been idealized for a long time by the Leftist leaders of Chile and the rest of the continent. In the end, Chile's Marxist leaders were unable to resist the example of the Cuban Communist Revolution. Caribbean tyrant Fidel Castro became the model, and Chilean Leftist leaders were intoxicated, like teenagers, by the actions and rhetoric of Che Guevara, who was calling for the creation of "multiple Vietnams" in Latin America. Chile's leftists failed to make the fundamental distinction between the noble objective of changing the world for the better and the use of violence. In Chile at the beginning of the 1970s there was too much poverty and underdevelopment, as well as monopolies and diverse injustices. Many idealistic people, especially the young, were searching for a revolution. The great tragedy is that so many of Chile's Communist and Socialist leaders, who should have been more mature and politically responsible, pushed thousands of these young people-first with incendiary rhetoric, and later by government action - into the abyss of political violence. In this context, it is shocking to read the honest confession of a former Argentine guerrilla: "Today I can tell you how lucky we are that we were not victorious. Given our formation and our heavy dependence on Cuba, we would have sunk the continent in general barbarism. One of our watchwords was to turn the Andes into the Sierra Maestra of Latin America. First we would have shot the soldiers, then the opposition, and then any of our comrades who opposed our authoritarianism" (Jorge Masetti, El Furor y el Delirio, 1999). Allende's response to the Resolution was not the only one in which he showed his confusion about the meaning of the Rule of Law in a democracy. The Allende administration had developed a most unusual juridical theory of "legal loopholes," by means of which it had embarked upon the nationalization of a large number of private businesses of all sizes. In 1973 the Supreme Court reproached him for assuming powers belonging to that body, which resulted in an acrimonious exchange of letters. Thus, on May 26, 1973, in protesting at the administration’s refusal to comply with a judicial decision, the Supreme Court addressed the President in a unanimous decision: "This Supreme Court is obliged to express to Your Excellency, once again, the illicit attitude of the administrative authority in its illegal interference in judicial matters, such as putting obstacles in the way of police compliance with court orders in criminal cases; orders which, under the existing law of the country, should be carried out by the police without obstacles of any kind. All of this implies an open and willful disregard for judicial verdicts, with complete ignorance of the confusion produced in the legal order by such attitudes and omissions; as the court expressed to Your Excellency in a previous dispatch, these attitudes also imply not just a crisis in the rule of law, but also the imminent rupture of legality in the Nation." Allende, in a public speech a few days later, responded in this way: "In a time of revolution, political power has the right to decide, at the end of the day, whether or not judicial decisions correspond with the higher goals and historical necessities of social transformation, which should take absolute precedence over any other consideration; consequently, the Executive has the right to decide whether or not to carry out the verdicts of the Judicial Branch." Thus, by the middle of 1973, the anti-democratic exercise of power by President Allende and his ministers had led not only to an open constitutional conflict between the Administration and the Legislative Power as evidenced by the Chamber Resolution, but also to a serious collision between the Administration and the Supreme Court. At this point, it is important to make clear that although the growing economic crisis was producing general misery and malaise-annualized inflation above 300 percent, rationing, a balance-of-payments crisis, growing unemployment, hopelessness-and although the crisis created an amplifying effect for these institutional conflicts, that was not the argument used for removing the Administration. The trigger was provided by the fact that the country had becomed "an armed camp" and Chile was slouching towards a civil war. (An important book that confirm this reality is that of James Whelan, Out from the Ashes.) Oscar Waiss, director of the government gazette (the "Diario Oficial") and an intimate friend of Allende, reflects in this statement the level of extremism reached by some of the UP leaders during the winter of 1973: "The moment had come to throw away all legalistic fetishism, to sack the military conspirators, to remove the Comptroller General, to intervene the Supreme Court and the Judiciary, to confiscate the El Mercurio newspaper and the whole pack of counterrevolutionary journalistic hounds. We must hit first, since he who hits first hits twice." ("Internacional Politics," No. 600, Belgrade, April 1975). 3. Frei leads the opposition and opt for the removal of Allende Salvador Allende became President of Chile after the failed administrations of Jorge Alessandri (1958-1964) and Eduardo Frei Montalva (1964-1970). Both governments were incapable of changing Chile's strategy of development, which had generated such mediocre economic growth that it was impossible to defeat misery and to create a horizon of prosperity for all Chileans. And both governments cleared the way for the violation of property rights, which are an essential foundation of a free society. Oscar Godoy, Director of the Institute of Political Science at Chile's Universidad Católica, argues that "the responsibility of the parties of the Right in the rise to power of the UP is that they did not know how to defend the institutions of the liberal State in a timely and vigorous way. For example, the defense of property rights was minimal, because those rights were being systematically surrendered. When the Right had the chance to recover, with Jorge Alessandri, it proved itself impotent against the novelty of the Christian Democratic movement and against socialism and it took its weakness to extremes. Lamentably, there was a dearth of public men on the Right who were ready to defend their plans with the same vigor that the socialists defended theirs. The campaign of Jorge Alessandri made multiple concessions to hide the true nature of the liberal project. At the time, there was much fear in expressing the words market, competition, individualism, etc. This was a capitulation which made it weaker still." (La Epoca, September 4, 1995). Weakening of property rights in Chile began, in effect, with the constitutional reform instigated by the Alessandri administration with the goal of initiating the Agrarian Reform. The warnings of Recaredo Ossa, former president of the National Agricultural Society, were prophetic, though ignored: "The rupture of constitutional guarantees with respect to agriculture is only the beginning of the breakdown of our democratic system. What is done today to this branch of production will be done tomorrow to urban property, mining companies of all sizes, trade, and all household goods. And furthermore the Constitutional Reform is the pilot project on the way to the abolition of property rights. Some people show no concern at the introduction of this wedge, but the crack will soon become an immense crevice, through which property itself will disappear." (Radio broadcast, reproduced by El Mercurio, January 6, 1962) The Frei administration took the country a long way in that direction, committing two other serious errors of public policy. In the first place, the administration responded weakly to the rise of political violence, and it was especially unfortunate that it did not react vigorously to defend democracy and the rule of law when the Socialist Party declared itself to be a partisan of armed struggle in its Congress of Chillán in 1967. And secondly, the administration's Agrarian Reform multiplied violations of property rights by expropriating thousands of agricultural properties without paying fair compensation. Furthermore, the Frei administration allowed the proliferation of de facto expropriations ("tomas") of other people's properties by groups of agitators. Such "tomas" under the Frei government included universities, municipalities, hundreds of agricultural properties, real estate, highways, industries, a military barracks, and even the Cathedral of Santiago. In this climate, it was not surprising that some parties on the Left sensed that taking total power was also feasible. With the failure of Alessandri's "right-wing" administration, and the failure of Frei's "centrist" one, and in the absence of a democratic left, the result was predictable. In August of 1965, Frei himself had said, "If my administration fails, we will have a government of the extreme left." (Leonard Gross, The Last, Best Hope, 1967). What was as unpredictable as it was extraordinary was Frei´s performance after he left the presidency. A man who had been very fearful of appearing to be "anti-communist," Frei decided on this crossroads of history to risk everything to save Chile from falling into the hands of a Marxist dictatorship. It should be noted that he lived under the weight of the very heavy accusation that was made against him at the end of the 1960s, namely, that if he turned the government over to Allende, he would go down in history as the "Chilean Kerensky." Frei chose to remain in Chile after stepping down. By remaining he put his life in great danger, a fact made clear when Leftist terrorists assassinated his ex minister and political heir, Edmundo Pérez Zujovic. Frei´s action can be contrasted with the attitude of Alexander Kerensky, who escaped from St. Petersburg and died in New York (in 1970, the year Frei handed power over to Allende), writing books about how he was unable to stop a band of daring Bolsheviks from seizing Russia by force. The former president must have known that his posture would be criticized not only by his adversaries, but even by many of his friends, as was effectively done by his former Minister of the Interior, Bernardo Leighton, who would attribute Frei´s attitude to "a true burden of conscience about the triumph of the UP government"(Letter to Frei, June 26, 1975). Frei returned to the political arena, running in the Senate elections of March 1973 as senate candidate for Santiago. Once elected, he accepted the presidency of the Senate, and therefore transformed himself into Allende’s principal adversary. Senator Patricio Aylwin, a very close collaborator of Frei, had on May 12, 1973, presented a successful motion in the Christian Democratic Party General Assembly, accusing the Allende administration of trying to establish a “Communist tyranny” in Chile. Later, on August 22, Aylwin would revise the proposed Resolution, wrote its conclusions, and without doubt after obtaining the agreement of Frei (the undisputed leader of the Christian Democrats), sent the final version for approval to Orrego. Furthermore, it was Aylwin who made the public reply after Allende had responded to the Resolution. The leaders of the National Party, headed by its valiant and combative president, Sergio Onofre Jarpa, had very early on denounced the Allende administration’s growing disregard for the Rule of Law. Nevertheless, it was the posture assumed by Eduardo Frei, with rare strength, that tipped the balance among the military commanders in those crucial months of 1973. As President of the Senate, he was the leader with the greatest ability to call the opposition together, and he was also the Chilean leader with the most international prestige. Indeed, the London Times judged him to be “the most important political personality in Latin America." Testimony exists showing that Frei had arrived at the conviction that only the Armed Forces could keep Chile from becoming a second Cuba. The highly significant “Rivera Memorandum” describes a meeting on July 6, 1973 between Frei and the leadership of the Chilean Industrialists Association (Sofofa), the largest trade association of Chilean manufacturers. In that meeting, Sofofa’s leaders stated that “the country was disintegrating and that if urgent measures were not taken, Chile would fall under a bloody Cuban-style Marxist dictatorship.” The response of Eduardo Frei is revealing: "There is nothing that can be done by myself, by the Congress, or by any civilian. Unfortunately, this problem can only be solved with guns... I fully share your apprehensions, and I advise you to express them plainly to the commanders-in-chief of the Armed Forces, hopefully today." Frei’s most extensive testimony on these matters is his letter of November 8, 1973 to the President of the International Christian Democrat Party, the Italian politician Mariano Rumor. There Frei reiterated the accusations of the Resolution of the Chamber of Deputies: "They were implacable in their efforts to impose a social model clearly inspired in Marxism-Leninism. In order to achieve their ends they twisted the laws or openly trampled over them, ignoring the Judicial Branch. In their attempt at domination, they even tried to substitute a Popular Assembly in the place of the Congress as well as trying to create a system of Popular Tribunals, some of which actually began to operate. This was denounced publicly. They also attempted to transform the entire educational system, based on a process of Marxist indoctrination. These attempts were vigorously rejected, not only by the democratic political parties, but by unions and organizations of every kind, and with regard to education that meant the protests of the Catholic Church and of all of the Protestant faiths, who all made their opposition public. Faced with these realities the Christian Democrat Party could not remain silent. It was its duty—which it fulfilled—to denounce a totalitarian plot which was always disguised behind a democratic mask in order to buy time and to cover up its true objectives." In a conversation with a journalist from the Spanish newspaper ABC, published October 10, 1973, Frei had already made severe judgements against the UP and had fully justified the military intervention: "The country has no way out other than a military government”; "The world does not know that Chilean Marxism had at its disposal arms superior in number and quality to that of the Chilean Army "; "The Armed Forces were called, and they complied with a legal obligation, because the executive and judiciary, the Congress and the Supreme Court, had all publicly denounced the presidency and its regime for destroying the Constitution"; "Civil War had been prepared by the Marxists "; "It is alarming that in Europe no one understands the reality: Allende left this nation destroyed." A third key text from Frei is the prologue he wrote to the book by Christian Democrat political scientist Genaro Arriagada, with its eloquent title: “From the Chilean Way to the Way of Insurrection” (1974). There Frei made similar declarations to those contained in the letter to Rumor, and as an epigraph for his prologue, Frei chose this warning from Pindaro: "Even the weakest person can destroy a city to its foundations; but it is a very difficult business to raise it up again." 4. The inevitable outcome Professor Richard Pipes of Harvard University has written that with the Resolution, "the Chamber had requested that the Armed Forces restore the laws of the country. Obeying that mandate, 18 days later the Chilean military, led by General Augusto Pinochet, removed Allende from office by force” (Communism: A Brief History, 2001). Two days after the removal of Allende on September 11, 1973, the influential British magazine, The Economist, published an editorial titled, "The End of Allende,” the content of which is so revealing that it merits full analysis. The magazine was very clear in assigning responsibility for the rupture that occurred two days earlier: “The temporary death of democracy in Chile will be regrettable, but the blame lies clearly with Dr. Allende and those of his followers who persistently overrode the Constitution.” The editorial goes even further and assigns to Allende the responsibility for the ensuing violence: "The fighting may have barely begun. With most of Chile's links with the outside world still severed, it was difficult to take the full measure of the apparently continuing violence. But if a bloody civil war does ensue, or if the generals who have now seized power decide not to hold new elections, there must be no confusion about where the responsibility for Chile's tragedy lies. It lies with Dr. Allende and those in the marxist parties who pursued a strategy for the seizure of total power to the point at which the opposition despaired of being able to restrain them by constitutional means.” The description of the situation in Chile given by the British publication could have been written by any of the deputies who approved the Resolution: “What happened in Santiago is not an everyday Latin American coup. The armed forces had tolerated Dr. Allende for nearly three years. In that time, he managed to plunge the country into the worst social and economic crisis in its modern history. The confiscation of private farms and factories caused an alarming slump in production, and the losses in state-run industries were officially admitted to have exceeded $1 billion last year. Inflation rose to 350 per cent over the past twelve months. Small businessmen were bankrupted; civil servants and skilled workers saw their salaries whittled away by inflation; housewives had to queue endlessly for basic foods, when they were available at all. The mounting desperation caused the major strike movement that the truck-drivers started six weeks ago. But the Allende government did more than wreck the economy. It violated both the letter and the spirit of the Constitution. The way it rode roughshod over Congress and the courts eroded faith in the country's democratic institutions.” At the time, The Economist was one of the very few foreign media that mentioned the crucial Resolution of August 22: “A resolution passed by the opposition majority in Congress last month declared that ‘the government is not merely responsible for isolated violations of the law and the Constitution; it has made them into a permanent system of conduct.’” For the British magazine, “the trigger for the coup was provided by the efforts of left-wing extremists to promote subversion within the armed forces. Two leaders of Dr. Allende's Popular Unity coalition, Sr. Carlos Altamirano, the former Socialist Party Secretary-General, and Sr. Oscar Garreton of the Movement of United Popular Action, were named by the navy as the ‘intellectual authors’ of plans for mutiny among the sailors in Valparaiso... The feeling that parliament had been made irrelevant was increased by violence in the streets (almost on a Belfast scale) and by the way the government tolerated the growth of armed groups on the far left that were openly preparing for civil war.” The Economist fully justifies the military intervention when it argues that, “the armed forces moved only when it had long been clear that there was a popular mandate for military intervention. They had to move in the end because all constitutional means had failed to restrain a government that was behaving unconstitutionally.” And it made an important clarification: the "coup was home-grown, and attempts to make out that the Americans were involved are absurd to those who know how wary they have been in their recent dealings with Chile." Alexander Solzhenytsin once stated that "Communism only stops when it hits a wall of resolution.” In the end, it was this civilian pressure that pushed the opposition political parties into approving the Resolution of the Chamber of Deputies, and then pushed the Armed Forces to obey the plea of the Resolution and remove by force the President who had been systematically violating the Constitution of the Republic. The generalized civil resistance that concluded with the Resolution of the Chamber of Deputies was the “wall of resolution” that Communism hit in Chile. That Resolution, therefore, constituted the death certificate of President Allende’s government. As was affirmed by one of the key men behind the Resolution and then-President of the Christian Democrat Party, Patricio Aylwin: "The Allende government had exhausted, with the greatest failure, the Chilean road to socialism and it was rushing towards an “auto-coup” in order to install a Communist dictatorship by force. Chile had been on the edge of experiencing a “Prague Coup,” which would have been tremendously bloody, and the Armed Forces did nothing other than head off that imminent risk" (El Mercurio, September 17, 1973). That was not an isolated declaration by the future President of Chile (1990-1994). One month later, Aylwin confirmed his thinking: "The truth is that the actions of the Armed Forces and the National Police were no more than a preventative measure which preempted a coup d’etat which, with the aid of armed militias and the enormous military power at the government’s disposal and with the collaboration of no less than 10,000 foreigners in the country, would have established a Communist dictatorship" (La Prensa, October 19, 1973). It is impossible, in the light of all those antecedents, not to conclude that the military intervention to remove President Allende was the result of a civil rebellion against tyranny. It was legitimate and inevitable, since, in the words of Vaclav Havel, a man whose country suffered under a Communist dictatorship for decades, "evil must be confronted in its cradle, and if there is no other means of doing it, then it must be done with the use of force" (New Yorker, January 6, 2003). The facts therefore demonstrate that: a) President Salvador Allende was primarily responsible for his own fall from power, having committed political suicide by declaring himself to be in rebellion against the Constitution of the Republic. b) Eduardo Frei Montalva, then President of the Senate, was the preeminent leader of a civil resistence movement which concluded with the plea for the intervention of the Armed Forces. c) The Armed Forces, in removing the Socialist-Communist government, obeyed a moral and political mandate given by the Chamber of Deputies, a chamber of the same Congress that in 1970 had elected Salvador Allende President of Chile. A surprising thing happened on that cold night of August 22, 1973, immediately after the members of the Chamber of Deputies had finished voting on the Resolution. Several of the Christian Democrat and National Party members began singing the National Anthem. And they were joined by others until the entire Chamber was on its feet, singing the anthem. Somewhere in that love for Chile, shared by all, a glimmer of hope survived. POSTCRIPT I have written this essay as a contribution to the cause that “never again” should democracy be destroyed in Chile, and for that it is indispensable to understand how political violence led to the inevitable breakdown of 1973. I would like to propose for the future three fundamental principles in this regard: a) Under no circumstance, with no justification, and in no form, should a group propose, much less initiate, violence as a mechanism of economic, social, or political change under a democratic regime; b) If violence has been initiated by any one sector, it should be immediately blocked by the incumbent administration, within the law but applying all of the force of that law; and, c) Political and civil society must unanimously reject those who propose and use violence, and they must support the government when it firmly suppresses that violence. |

|

2010 © www.josepinera.org