The Fascinating Reagan Letters

By Andrew Sullivan

[Sunday Times, September 28, 2003]

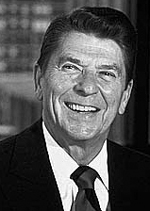

Public life is a strange thing. We think we know people; we judge them; we psychoanalyze them; we parody and idolize them. I grew up watching Spitting Image versions of Ronald Reagan. He was a senile, slobbering fool. He was basically illiterate, knew nothing and wanted to blow up the planet. At best, he was an actor whose grasp of politics or economics or diplomacy or anything faintly resembling intellectual life was close to zero.

Even when the extraordinary success of his policies sunk in - the peaceful victory of the West in the Cold War, the resuscitation of the American economy - it was still hard to think of him as truly the architect, someone self-aware, self-critical, astute.

And now we have the letters. Hundreds and hudnreds of them - published last week and extracted in Time magazine. The headlines were all about his confession of sexual anxiety, and how he managed to overcome feelings of sexual guilt in part by referring to the (now debunked) research of Margaret Mead on the Polynesians. But when you actually start reading the letters, it's hard not to be taken aback by something else.

Reagan was a highly articulate, well-read and subtle man. The range of his interests, the extent of his knowledge and understanding of world events and history, his grasp of detail are all completely counter to the image we have long held. From developments in Communist China to the latest economic figures, from isolated dissidents he helped free from the Soviet Gulag to an intricate account of how the Iran-Contra affair escaped his political management, we find a man far more clued in than we had been led to believe. Private letters are among the most intimate of a public person's output. They can reveal more about a person than many other public documents. And in this case, they really do.

He was extraordinarily humble. Even while in office, he would take hours out of his day to hand-write detailed and earnest replies to complete no-bodies. After a few hours devouring the book, I couldn't find a single letter in which he didn't try to end on a conciliatory or friendly note.

The intelligence of the man is undeniable. There's a detailed letter setting Professor Arthur Laffer right on petrol taxes; there's a complicated analysis of spending trends in his administration to another irked correspondent; there's a long explanation of the crossed wires that led him to pay tribute to dead SS Officers at a cemetery in Bitburg, Germany. And there's sharp honesty about his strategy for defeating the Soviets as early as 1982. He tolerated the deficits, he explained, for a long-term reason: "I don't underestimate the value of a sound economy but I also don't underestimate the imperialist ambitions of the Soviet Union... I want more than anything to bring them into realistic arms reduction talks. To do this they must be convinced that the alternative is a buildup militarily by us. They have stretched their economy to the limit to maintain their arms program. They know they cannot match us in an arms race if we are determined to catch up. Our true ultimate purpose is arms reduction." At the time, he was pilloried as a warmonger by the nuclear freeze movement. Later, critics were stunned by his apparent volte-face into peace-making. But he knew what he was up to from the beginning. And now we know for sure.

Of whom is he most critical in private? The press, of course! His recurring metaphor - actually, it's a constant metaphor - is "lynch mob." And if you enter into the world of these letters, and the genuinely well-intentioned, kind and humane man behind the caricature, you begin to get an idea of why he loathed them. But he's also aware of how irresistible the media can sometimes be. In a letter to Nixon, he recounts, "I'm always reminded of the Hollywood days and how the people in our business would read the gossip columns and your first reaction was always how dishonest they were about yourself, but two paragraphs later you're believing every word when they talk about someone else."

Of course, this world reflects his own view of reality, and that of the editors of the volume. But it still runs directly counter to some preconceptions. What, for example, are we to make of the stereotype of a lazy president, always napping, watching movies rather than preparing for summits when you come across a passage like this: "This president doesn't have a nine to five or nine to three schedule, nor does he have a five day week. I take the elevator up to the living quarters in the White House with reports, briefings, and memorandums for which there is no reading time during the day. I spend my time until 'lights out' trying to absorb all of that. The same is true of the weekends - when I'm not attending a summit conference or making a speech somewhere." Reagan's biographers tend to back him up on this. But Reagan himself used to joke about his own idleness. In fact, it was a standard laugh-line of his. Was it all a ruse?

But the tenor of a man is something letters do reliably reveal: and there's an old-world civility to Reagan that has been lost in contemporary American politics, a dignity and empathy with middle America that is as rare as it is touching. His diligence in hand-writing long letters to obscure pen-pals, even while holding down the most stressful and busy job on the planet, leaves me slack-jawed. And then there's the light way he wears his Christian faith and the winning way he had with words: "During my first months in office," he wrote an old friend, "when day after day there were decisions that had to be made, I had an almost irresistible urge - really a physical urge - to look over my shoulder for someone I could pass the problem on to. Then without my quite knowing how it happened, I realized I was looking in the wrong direction. I started looking up instead and have been doing so for quite a while now."

I wonder what, in a few decades' time, we'll be finding out about George W. Bush.